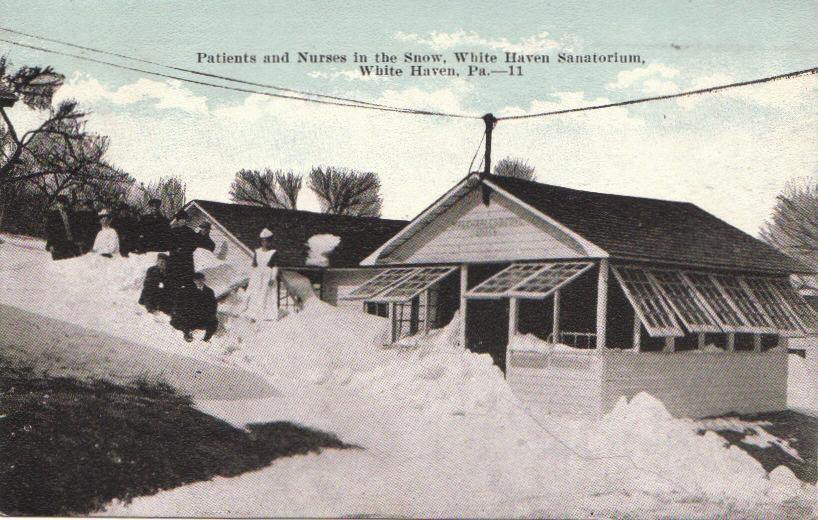

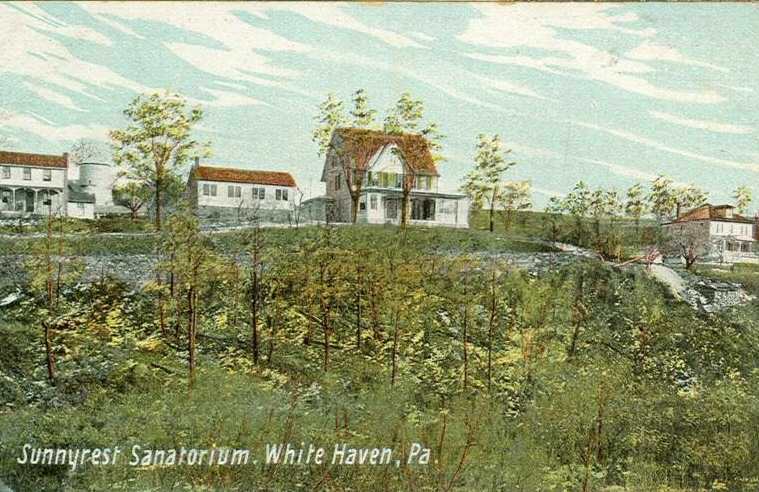

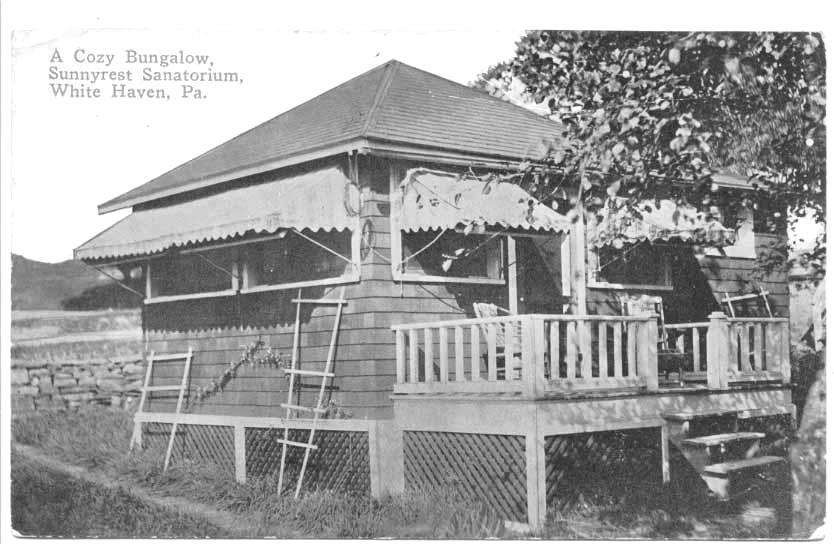

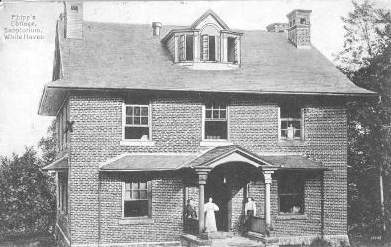

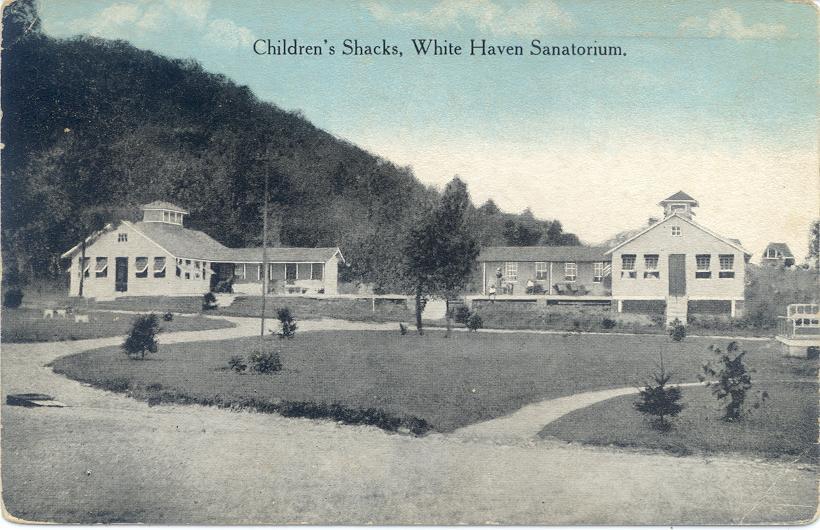

In the late 19th century, a group of philanthropists were seeking a location for an institution constructed to specifically treat people suffering from "consumption," a bygone term for tuberculosis. In the days before vaccinations and antibiotics, cold, dry air was believed to have a therapeutic effect for sufferers of TB. The town of White Haven offered such a climate, in addition to other geographical benefits. White Haven was easily reached by train from New York; at the same time, it was isolated enough to provide a measure of containment against the spread of TB.

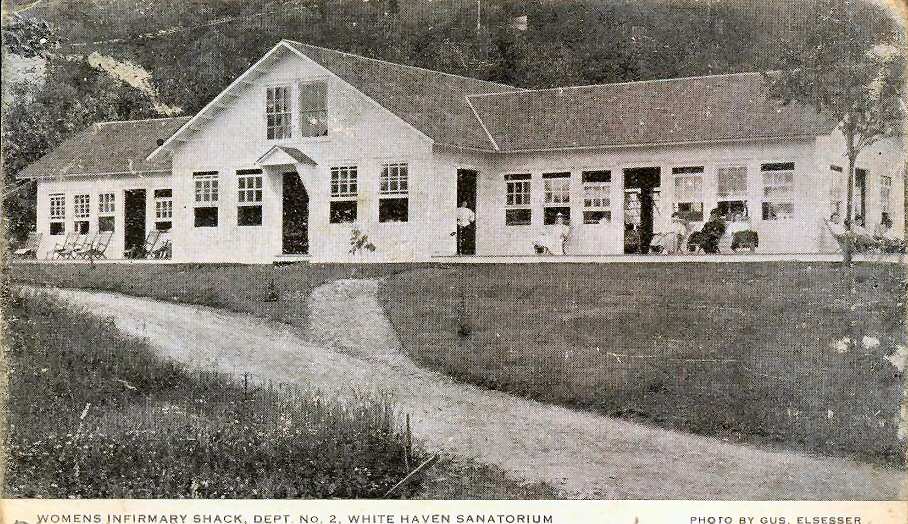

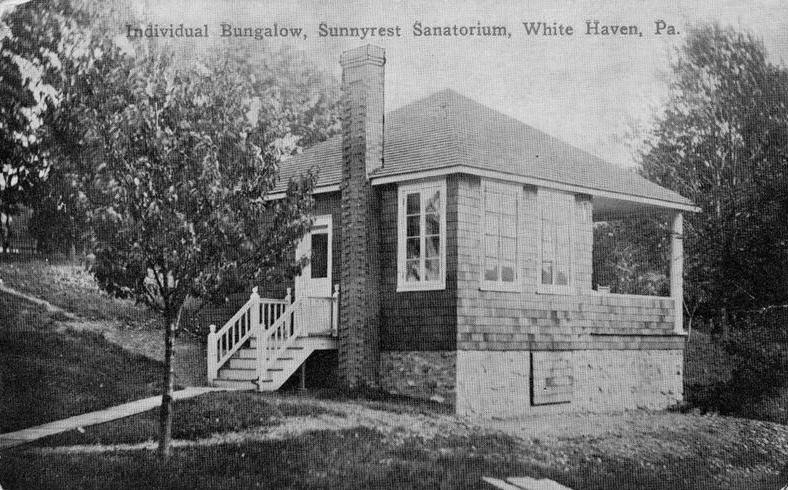

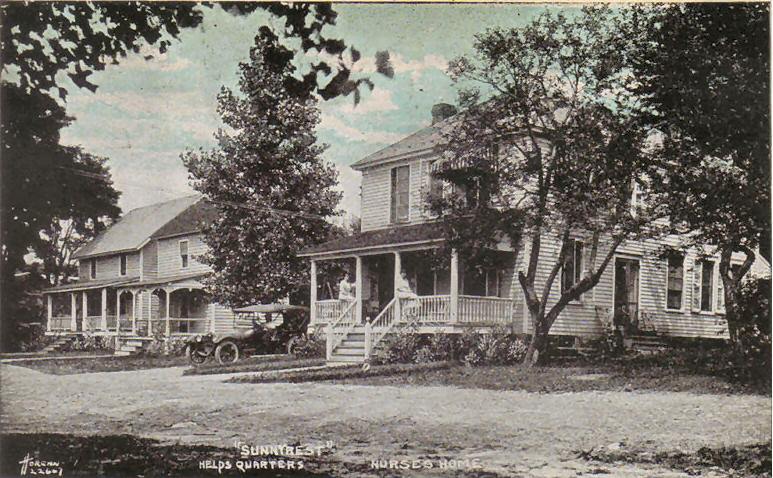

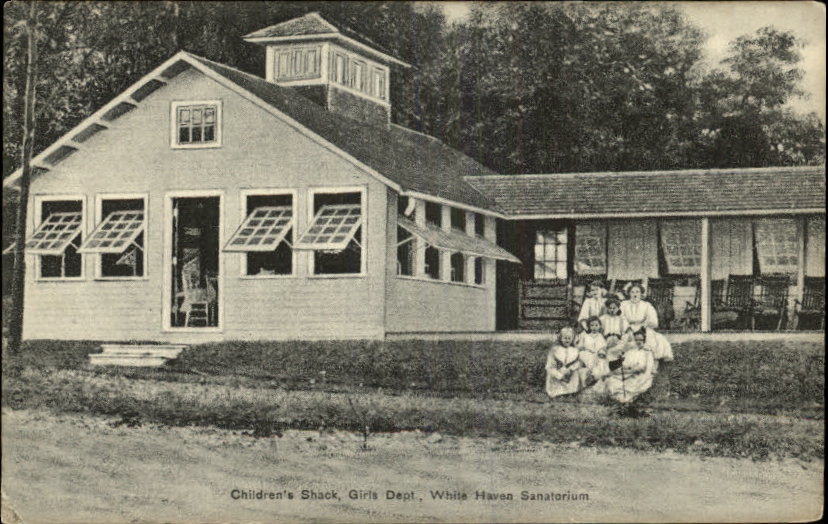

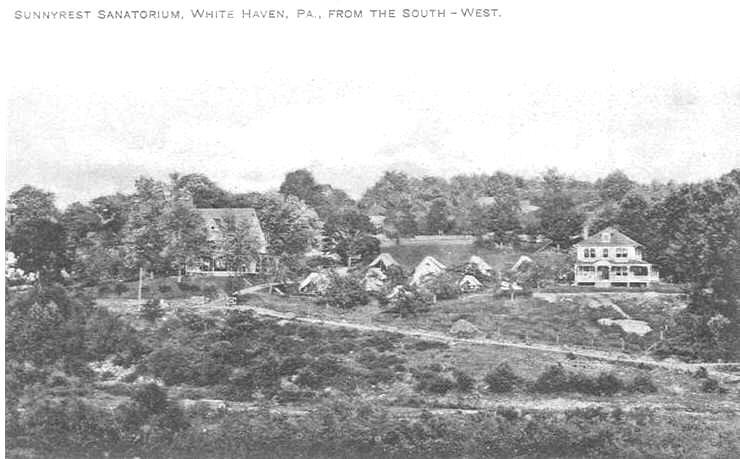

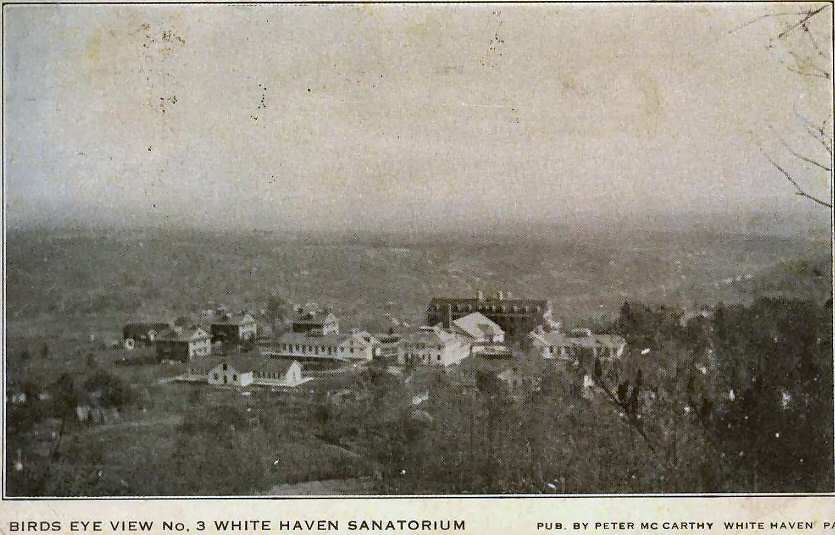

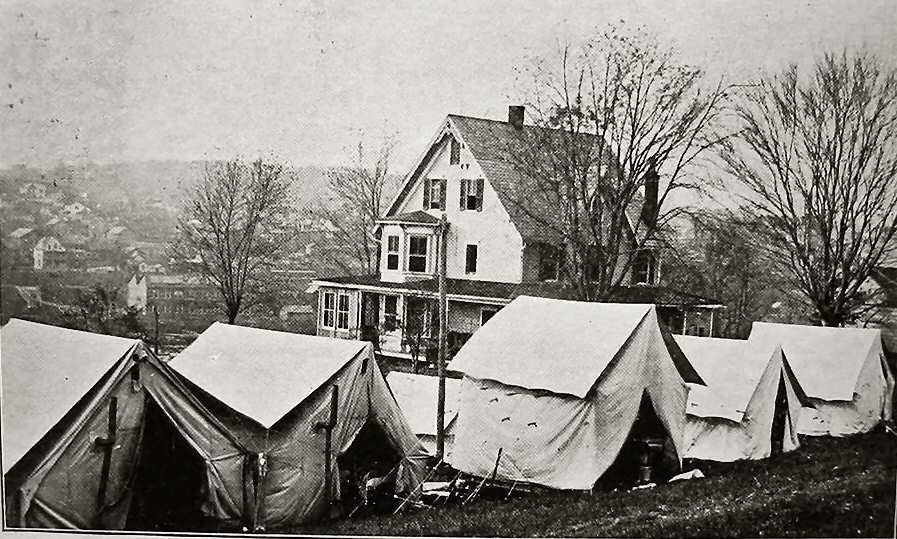

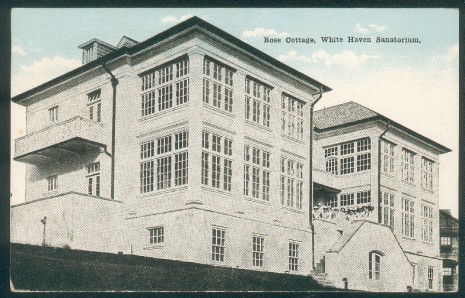

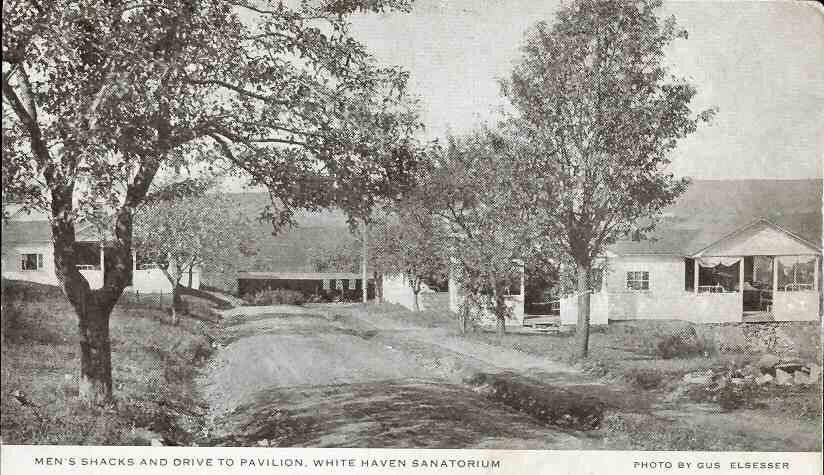

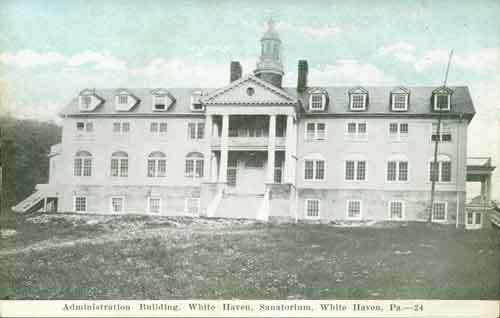

The White Haven Sanatorium was founded in 1907 with Dr. Lawrence Flick as its head. Initially, the Sanatorium consisted of only a few buildings, but as the spread of tuberculosis reached epidemic proportions, the facility expanded. Over the next thirty years several new buildings were constructed, including additional wards and a nursing school. The rapid growth of the Sanatorium quickly outstripped the 400 kilowatt capacity of the White Haven Light, Heat & Power Company, mandating the construction of a dedicated coal-to-steam power plant to supply the growing medical complex with electricity.

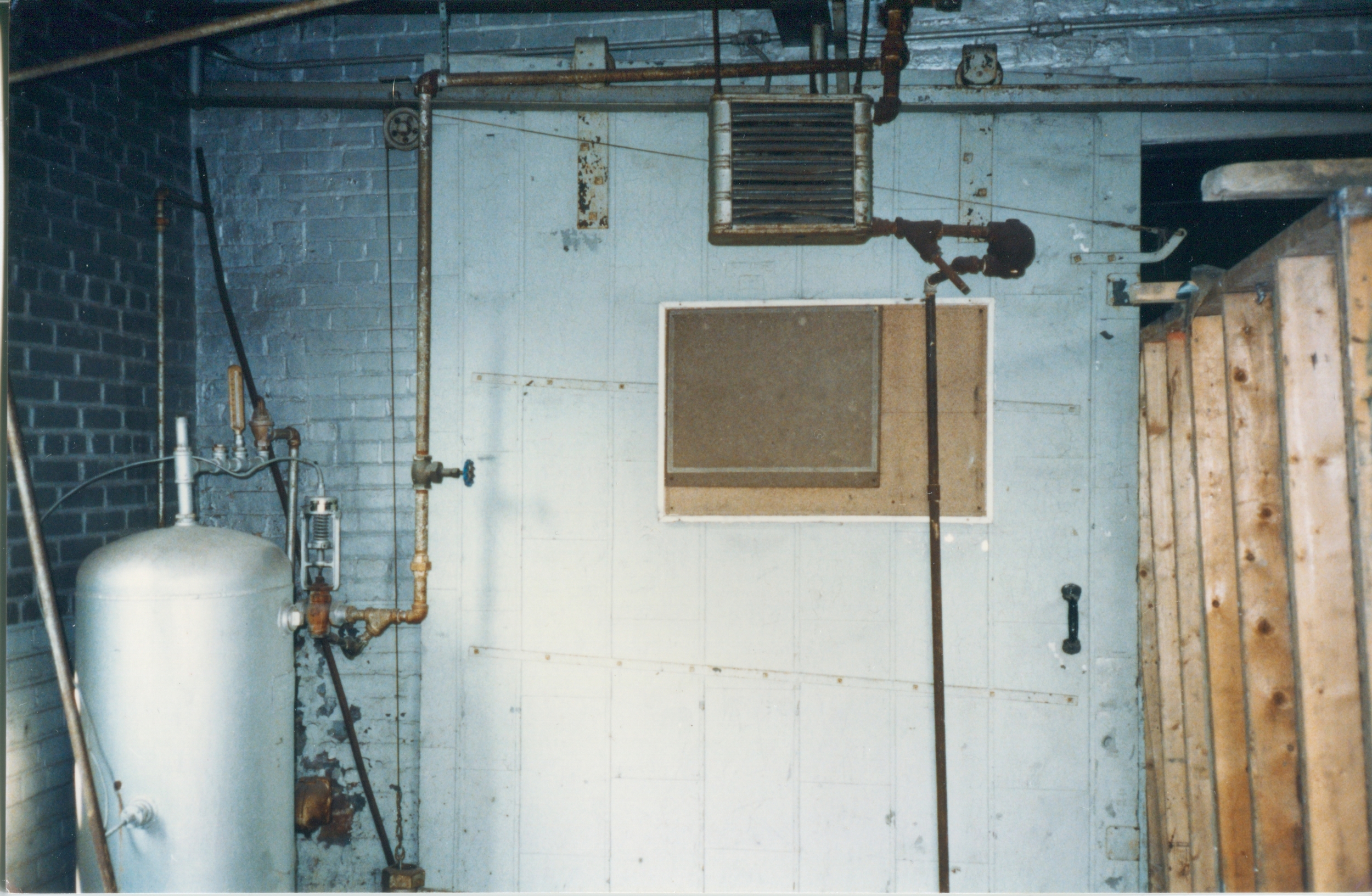

In 1938, wealthy industrialist Pierre Dupont donated $125,000 to the center in gratitude for the care given to his tuberculosis-afflicted personal secretary. These funds were used to further expand the power plant. Prior to its renovation, the plant had encompassed only what are today the bar and the lounge; Dupont's gift provided for what are now the dining room and state-of-the-art kitchen. The variations in brickwork between the older and newer walls clearly illustrate the fact that this structure evolved in stages, a fascinating historic characteristic we have taken great care to preserve.

Over the next couple decades, the Sanatorium underwent many changes. It was donated to the Jefferson Medical College in 1946 for the continued care of tubercular patients, but, thanks to the introduction of streptomycin and modern immunization techniques, the number of TB cases was in a sharp decline, a fact that boded ill for the Sanatorium. Out of business, it shut down in 1956.

Yet it would not see its doors closed for long. That same year, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania purchased the estate to provide care for the mentally challenged, and the complex, now called the Penn Hurst Center, entered the next phase of its existence. In 1960, the facility, stretched to capacity, was deemed insufficiently sized to accommodate an ever-increasing number of patients, so the State purchased property on the north side of I-80, and began construction of what is now the White Haven Center. By 1976, the old Sanatorium complex was completely vacant.

1989 found the power plant being renovated into a restaurant. During this process, much of the existing construction and hardware was preserved to create a singular atmosphere. The impressive assortment of valves, boilers and fire doors on display, in conjunction with exemplary cuisine, make for an incomparable dining experience.

Restoration Process

The Surprisingly Stunning Afterlives of Old Coal Plants

As the U.S. moves toward greener electricity production, old coal-fired power stations are being repurposed for the new demands of a cleaner economy.